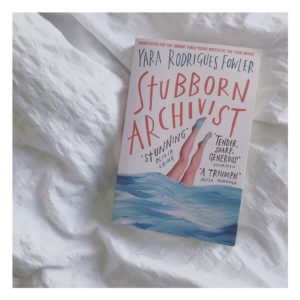

Getting your debut novel published: a Q&A with Yara Rodrigues Fowler

Hazel: I’d love to know what your writing routine is like. I’m a bit obsessed with writers’ daily routines and rituals.

Yara: I don’t really have a daily routine that’s fixed, and it’s changed because of lockdown, obviously. I wrote the first bits of Stubborn Archivist over a few years when I was doing a Masters in Comparative Literature, which was the first time I could study Brazilian literature or Caribbean literature. I did a lot of translation theory, which led me to a lot of how I think about bilingual writing and fragmentation. I was working part-time at the time as well, so I would try to go to the library on the days I wasn’t working. Since Stubborn Archivist came out, I’ve lived at home again so, financially, I’ve just been able to afford to move out and go freelance again. For a while, I was working full time and editing Stubborn Archivist, and I’d have no holidays. I’d take a holiday and write on the holiday or at the weekends. I didn’t tell my boss because I was scared they might fire me. I didn’t have a routine, I was burnt out. I don’t recommend that, I think that’s really awful.

So now, I have to do freelance work — most of the time I get to do my own thing, and I try to wake up and go to sleep the same time every day. Obviously I have to try and earn money, but if I get behind on my emails, I try to forgive myself, because I think the nature of having a really big project that consumes all of your time, sometimes everything else does fall to the side. It’s just a question of how much can fall to the side without repercussions. I write as much as I can and block out those days in my diary. Sometimes I’ll try and go away for a week or two, if I need a real intense burst. So, I don’t really have a routine, I just try to make time for writing and reading. Basically, as long as I’m making money and no one really hates me, it’s okay to let everything else fall to the side a bit.

I think that’s really interesting. You don’t set yourself a structure, really. It’s almost a bit more ad-hoc than that. I wonder how that compares to other people, because I know other people are a lot more rigid about it, a proper 9-5.

Yeah, and the thing is also I kind of have to be flexible. For money, I do a mixture of things; some teaching, some copywriting, and I can’t really choose when that work comes up, so I have to be a bit flexible. When I’m working from home, I do keep more or less from 9:30-6. If I need a nap, I’ll just take a nap.

"I didn't have a routine, I was burnt out."

You talked about the process for Stubborn Archivist. How did you go from finishing it to getting it seen by publishers, agents?

The first draft was 18,000 words, which is like an LRB long read, but I didn’t know how many words were in a book. The books I thought it was similar to were Sandra Cisneros’ The House on Mango Street, Junot Díaz—turns out he’s a bit of a creep—but his first book, Drown. I made a list of agents; I sent it to four young women at the start of their careers who did slightly experimental international stuff. I met with one and we signed, and she said let’s take it to publishers, who knows what will happen — why don’t you add an extra chapter, though? So I did, and we sent that out to publishers in September 2016. Lots of them came back being like “oh, we love the style”, “oh, we’re so interested in Brazil”, whatever. But they said it was way too short, and not a full enough narrative. I had a draft that was 50,000 words the next April. That was the part of my life where I was just not a human and I don’t think that was good. I wish I’d never done that, there was no rush, really. It was awful, because there was no guarantee that she would publish it. So I did that, and then she didn’t want to publish it. We sent it out to lots of publishers, and one of them did want to publish it — that’s Rhiannon Smith at Fleet, my UK editor. Once we signed, I asked if I could cut some words out. I do think it’s a better book for being fuller and longer, and I got better as a writer as well. The actual publishing and editing process is all quite slow, so you sign and you deliver the manuscript a year before publication.

I think it can be quite a radical thing to talk about money, because one of the things that I really didn’t understand was how much money we were talking about. When I signed with Fleet, I got £7,500 for UK rights minus North America. The US rights sold for a similar amount. They haven’t managed to sell the Brazil rights, which obviously breaks my heart. An advance means you get that money in three chunks: when you sign, when you deliver the manuscript, and when it’s published. You have to ‘earn that out’, and only after £7,500 worth of earnings on book sales, for example, do you start getting royalty cheques. Depending on what you’re writing, if you go on the hashtag #PublishingPaidMe, you can see what different people have got for different books. I think what I got was quite decent for a literary book. Sometimes when there’s an auction, that’s when people can just lose their shit and end up paying loads of money for a debut, but for context those advances were both from big publishers. If you sell your book to an indie press, you might get much less. As an experimental debut by an unknown author, Stubborn Archivist was considered a sort of gamble; on the other hand it’s a coming of age book about a young woman, so in that sense not wholly new ground…

"I think it can be quite a radical thing to talk about money, because one of the things that I really didn't understand was how much money we were talking about."

Did you know about that before you embarked on your journey?

No. I don’t know if it’s an English thing or a middle class thing but no one talked to me about numbers until there was actually a deal on the table. For Young Adult, sometimes you can get slightly bigger advances, and something that’s more “commercial” will get a much bigger advance – if you google a book name then there’s usually a bookseller article about the deal – you can see there if it mentions ‘six figures’ to get a sense.

Was that helped by your publishing house?

In terms of publicity and marketing, there are many different factors, it’s not as simple as big publisher = big publicity, although it can often mean that. So, I think how hard the people around you work will depend on what resources they have and how much they prioritise you – at a small publisher you might one of few authors, for example. I feel I had the best of both worlds – I really love the team at Little, Brown (Fleet is part of Little, Brown). Fleet is a small imprint and everyone on the team is about the same age and early-ish in their careers and I felt that it mattered a lot to everyone. My publicist, Hayley Camis, was nominated for an award for her publicity campaign and that made me really happy.

It was the first time in my life where I’ve been really respected as a member of a team, rather than just the most junior person at a communications agency or something, where everyone’s always being horrible to you. It was a really cool experience, I’ve never been in a work environment where people are really nice to me (laughs).

And this seems really obvious, but you have to treat the people working on your book with you with a lot of respect and care, because that’s just the right human thing to do, but also if your publicist doesn’t like you or your book, they’re not going to put it in the hands of everyone they meet.

"It was the first time in my life where I've been really respected as a member of a team"

Could you tell us about your second novel?

Actually, I haven’t finished the book at all, I’m about 70% of the way through. Maybe it’s just being a little bit older as well, but I don’t have that existential need to prove to the world that I can write a book. Which is part of what drove me before, which is fine, but I think I’m much less enthralled to thinking productivity is really important, or achievements are. I really enjoyed the book launch process and the events, but it’s also really nice to just be writing and living my life, and not be an author performing all the time.

It’s got two characters this time, and much more sex and history. In some ways it’s more traditional, in others it’s heftier and braver than SA.

Yara is one of the mentors on the Lit:Up 2020 mentoring scheme, and her novel Stubborn Archivist can be found here.