Room With a View: Creative Writing Exercises

Exercise One – In This Room

A key part of being a good writer is to really pay attention to your surroundings and to translate what you can hear, see, smell, touch, taste and feel into words so that other people can experience what you’re experiencing. Focusing on the five senses is an important skill to develop as it helps to make your writing richer and multi-dimensional. It’s also a great mindful tool for creating calm. Win win!

A key part of being a good writer is to really pay attention to your surroundings.

For this exercise, try to stay in the moment. Take in your surroundings. What can you see, hear, touch, taste and smell where you are today? Maybe there’s a smell of recently brewed coffee. Perhaps you can hear the birds tweeting outside or members of your family having an argument in another room. For touch, you might just want to focus on the feeling of your fingers on the keyboard or the way the paper feels beneath your arm or the pressure of one leg on top of the other, the feel of floorboards beneath your feet, or you could explore other feelings too. And if your mind gets taken away to a memory of another time and place as you notice a souvenir from a holiday on the desk, feel free to follow that thought too. Allow yourself to write whatever comes to mind and don’t think too hard about it. You can always edit it later.

Exercise Two – Room with a View

Windows and the views from them can be a rich source of inspiration for writing. They’re a boundary between one space and another, but a transparent boundary and a natural frame for writing. For this exercise, it’s probably easiest if you position yourself so that you can see out of particular window, but if you’ve got a good memory, you could also choose to write about a different view that you know well: maybe the view from a school window, or a holiday cottage that you might have visited. Follow the prompts below and allow your writing to get more fanciful and imaginative as you go on. Write in long sentences rather than making notes. Essentially, you’re constructing a poem, line by line.

You can also watch this video and follow the prompts included here:

- Something is straight in front of you. What is it?

- What’s off to the left?

- In the corner of your view, what can you see?

- Remember the way it looked at a different time in the past.

- Something is unusual today. What is it? Maybe something is missing, or present when it isn’t usually there.

- What is out of view (over the hedge, across the road)?

- What’s happening further away – on the other side of the village or the city?

- What about over on the other side of the world?

Exercise Three – The Witness

Let’s turn our attention from writing poetry to writing fiction and imagine a story in which a character observes the world from their window. Perhaps they’re a person who loves to be nosey, or someone who simply enjoys watching the world go by. Maybe, in your writing, you might have a whole cast of characters that the main protagonist sees: the woman who walks the dog at the same time every day, the man who pushes the pram, the postman or woman. Or, you might want to focus on one particular person and one particular incident.

Effective fiction tends to focus around change so see if you can incorporate this into your story. Maybe the main character sees something that changes their perception of the world in some way or perhaps they see something that literally changes their world. Perhaps it’s something that they shouldn’t have seen and perhaps their decisions about what they do with that knowledge will drive the story. Maybe the change is simply that the woman stops walking the dog or that the post stops arriving. It’s up to you.

Effective fiction tends to focus around change so see if you can incorporate this into your story.

Here are a few suggestions to get you started:

- The post gets delivered to the wrong house and a person who hasn’t left their home for years has to take it to the rightful owner.

- Someone witnesses a robbery.

- A character sees two people having a fight and has to decide whether to intervene.

- Someone overhears a conversation that they shouldn’t have heard.

- A character sees or has an encounter with some unusual wildlife – maybe a badger or a fox

Exercise Four – Picture This

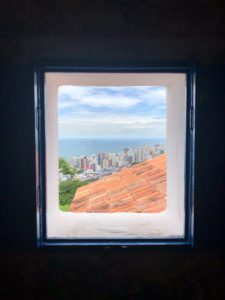

In case you’re tired of looking out of your own windows at your own views, we’ve provided some different views for you to look at. Hopefully they might inspire you.

For this exercise, simply take one of the photographs and imagine yourself into the scene. You might be a character who is looking out of the window, or you might be someone in the scene beyond the window.

Use the following questions to help you to develop the character that you’re writing about. You might want to write a piece of fiction, but you could also write a poem about, or from the viewpoint, of the character. Most stories are driven by the desires of the main character and the obstacles that you, the writer, put in their way. You might want to think about that as you write.

- Who is the character? (Name, age, nationality)

- What are they doing here?

- Where are they going? Or where have you been?

- Who are they with or who are they waiting for?

- What are they afraid of?

- What do they have in your pocket or bag?

- What do they want most in the world?

- What is their biggest regret?

- Who is their best friend?

- What is a secret that they haven’t told anyone?

Exercise Five – Objects

We’re surrounded by objects in our homes and what can seem ordinary and boring can soon be transformed into something interesting if we bring our attention and imagination to it.

For this exercise, pick an object from the room where you’re sitting and use it as the starting point for a piece of writing.

You might want to tell the literal story of what it is and where it came from or you could make it the centre of a fictional piece. Maybe that little box from your holiday in Spain is actually a repository for all of the secrets of the universe, or perhaps your notebook is enchanted and everything you write in it becomes true.

Maybe that little box from your holiday in Spain is actually a repository for all of the secrets of the universe?

Another exercise to try is to write from the point of view of the object. How does it feel to be the necklace that no-one very takes out of the jewellery box or the book that someone bought just to show off but which never gets opened?

Maybe you could write about two objects and their relationship. Perhaps the salt pot has a vendetta against the pepper pot or maybe the fork is in love with teapot.

Have fun with it.

Editing

“It is perfectly okay to write garbage–as long as you edit brilliantly.’ C. J. Cherryh

Editing is a fundamental part of the writing process. Some writers enjoy the first burst of creativity more than editing, but others love that process of stripping out the unnecessary parts of their work and shaping it into a finished piece.

I like to imagine editing as being a bit like sculpting; the finished story or poem is in there and your job as an editor is to chip away at the raw materials (your first draft) to smooth and polish the final work of art. Most writers write several drafts before they get to a piece that they’re happy with and, if you want to be a writer, it’s an important lesson to learn, that something is rarely finished at the first attempt. Invariably there’s a lot that can be done to improve a piece of writing and sometimes the finished article bears little resemblance to the piece you started out with. You write as a writer, but you need to edit as a reader.

Here are some tips to help you to improve your first draft.

General tips

- If you have time, leave your writing for a while before you start to edit it. That way you can view it as a reader.

- Read your work aloud. You’re bound to find yourself editing as you go along as you’ll sense which bits flow and which bits don’t.

- Give it to a few trusted readers to read. They will pick up things that you’re too close to see. Make sure you choose your readers wisely though. You don’t want the opinions of people who are too close to you who’ll be afraid of hurting your feelings (e.g. your mum) nor do you want people who are too critical or competitive. Other writers usually make for good critics as they know how precious your work is and they also know what to look for.

- Think about what the purpose of your writing is. Can you summarise it in a paragraph? What do you want your reader to think or feel after they’ve read it? It helps if you can keep this in mind as you edit and try to make sure that everything you write serves this purpose.

Fiction

- Is your opening the best one? Does it make the reader want to read on? It’s usually a good idea to get straight to the point and the action. Can you cut the first paragraph or page? Often we’re finding our own way into the story at the beginning and our opening isn’t the right one.

- That said, you want your reader to feel quickly located in your story and clear what it’s going to be about. You might find it helpful to think about the w’s: who, what, where, why and when. Can you convey the basics of this information quickly and succinctly?

- Lay some hooks and questions to get the reader interested at the beginning. It’s a delicate balance between giving enough information so that the reader isn’t confused, and leaving them intrigued and guessing what’s going to happen next.

- Are you showing rather than telling? This is a big topic and something you’ll be able to find out more about online. Generally-speaking, you want to feel like you’re in control of a movie set and that you, as writer, are directing the film, showing the reader the action as it unfolds rather than telling the story. The reader doesn’t want to hear your voice but the voices of the characters.

- Check your viewpoint. Usually it’s best to stick with one character’s point of view or to be very clear that you’re switching to another character (e.g. by starting a new page of chapter). Be careful not to flit between characters’ heads unconsciously as this can make the reader feel confused and disorientated. One way to check this is to ask yourself the question: ‘says who?’ at the end of every sentence.

- Check for repetition and see if you can use different words and phrasing.

- Use as few words as possible. You don’t need to explain things in several different ways e.g. don’t say, “ ‘I’m furious,’ screamed Jen, angrily.” One way of letting us know that she’s angry is enough.

- Where possible, avoid feeling words and show emotions in different ways e.g. with body language and physical sensations i.e. ‘she sank to the floor, her body wracked with sobs’ as opposed to ‘she felt really upset.’

- Don’t overdo it though. You don’t need to reference the tightness in someone’s chest every time they feel anxious and beware of mentioning the same things over and over again e.g. scratching chin, playing with hair, winking. How often do people really wink in real life?

- Avoid using too many adverbs and adjectives, especially adverbs.Often, you can replace an adverb by choosing a better verb e.g. instead of saying ‘he shut the door noisily’, you could say ‘he slammed the door.’

- Use dialogue to bring your prose to life and to show character rather than describing everything.

- Don’t overuse names. Unless it’s confusing, use ‘he’ and ‘she’.

- Be careful when choosing character names to choose names that sound very different. If your three main characters are called Ahmed, Abdul and Ahad, your reader is likely to get confused.

- Don’t feel you have to use complicated dialogue tags: ‘he said’ and ‘she said’ are usually better than ‘he expostulated’ and ‘she exclaimed’.

- Don’t give too much information and try to make it natural when you can e.g. a character wouldn’t say, ‘when Matt, my husband, came home from his work at the local hospital.’ She’d just say, ‘when Matt came home from work.’

- Check that you’re indenting each paragraph and each time a new person speaks.

- It’s generally accepted practice in the UK to use one inverted comma for dialogue and to put the punctuation inside the inverted commas e.g. ‘Are you coming for your dinner?’

Poetry

Editing poetry is a bit more complicated as poetry is more open to interpretation and individualistic stylistic choices but here are a few things you can look for.

- Read your poem out loud several times. How it sounds is as important as how it looks on the page.

- Are you using the perfect word? Poets think really hard about every word. They’re thinking about the sound and shape of the word as well as its meaning.

- Think about where you position your words. Does a line sound better if you turn it around?

- Consider line lengths and stanzas or the overall shape and balance of the poem.

- Think about which words go at the ends of the line. You probably don’t want to end lines with words conjunctions like ‘and’, ‘or’ and ‘because’.

- If you’re rhyming a poem, make sure you’re not just using a word because it rhymes. If you are, then think about a different way to say what you’re trying to say.

- Be consistent with your punctuation and capitalisation. Some poets use capitals at the beginning of each and some don’t. Either is ok but make sure you’ve thought about your stylistic choice.

- Does your imagery make sense? Poets often make use of similes and metaphors. One or two carefully-chosen metaphors are usually more effective that lots.

- Have you used other poetic techniques e.g. alliteration and assonance? Could these be strengthened?

- Think about your beginning and your ending. Are you starting and ending with two of your best lines?

Don’t forget to follow us on social for regular writing prompts and challenges; @thelitplatform / @theliteraryplatform.